AKALAN Kathak performances July 2022

https://www.lokmattimes.com/aurangabad/artists-enthrall-audience-in-akalan-kathak-performance/

This space is dedicated to sharing silent dialogues, memorable moments and unknown journeys of a dance-pilgrim

AKALAN Kathak performances July 2022

https://www.lokmattimes.com/aurangabad/artists-enthrall-audience-in-akalan-kathak-performance/

Kunal Ray

Kunal Ray

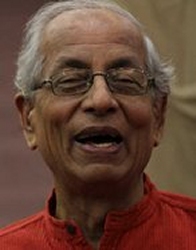

Filmmaker Adoor Gopalakrishnan

Films can play a significant role in understanding a dance tradition. Every dancer (or perhaps the better ones) is a living archive. They are custodians and repositories of a certain training, legacy, aesthetics and performance tradition. This came through clearly at the recently held festival of films on Indian classical and contemporary dance titled ‘Punaravalokan’ (looking back) held at Mahagami Gurukul in Aurangabad.

Think about Satyajit Ray’s Bala (1976) for instance, which isn’t a great film so to speak but nevertheless documents an important moment in Indian dance history. All the admirers of Kelucharan Mohapatra eventually turn to Kumar Shahani’s Bhavantarana (1991) to be captivated by the maestro’s matchless grace. Film therefore is a museum too. This observation was further corroborated by noted filmmaker and Dadasaheb Phalke award winner, Adoor Gopalakrishnan who was the chief guest at Punaravalokan and also participated in a conversation with the audience after the screening of two of his films at the festival, Kalamandalam Gopi (1999) and Dance of the Enchantress (2007).

Kalamandalam Gopi features legendary Kathakali maestro, Gopi, who was trained at the Kerala Kalamandalam. The film documents all the elements of Kathakali including make-up, costume, music and vividly portrays the training process an aspirant has to undergo. In a much later film, Dance of the Enchantress , Adoor showcases the evolution of Mohiniyattom through parallel stories of a teacher and her pupil. Both films also include some captivating performance footage shot at various locations across Kerala. These films not only serve as an exposition for the uninitiated but also play a major role in archiving dance heritage and some of its foremost practitioners.

In the conversation that followed the film screening, Adoor revealed his affinity for Kathakali. He said, “I started watching Kathakali from my mother’s lap. As a child, I used to be interested in the make-up of the artistes because each type denoted a specific character. Besides, there was drumming and singing. I gradually began to appreciate the importance of lyrics. My mother would explain the stories before the performance because you will not understand the recital without knowing the story.”

However, in his youth, Adoor was drawn to modern theatre. He rediscovered Kathakali much later. He informs, “There was a long gap in between. I slowly went back to follow Kathakali. The first such documentary I made was on a famous guru, Chenganoor Raman Pillai. He was almost 92 when I shot the film. Years later, I made this film on Gopi which captures him at his peak. I also made another film on Guru Ramankutty Nair who was Gopi’s guru. In this process, I realised why Kathakali ought to have been discovered in Kerala and not any other place.

Film on Krishnanattam

Adoor Gopalakrishnan also made a film on Krishnanattam, the precursor to Kathakali. He explains, “Both Krishnanattam and Kathakali have their origins in Koodiyattam which is being performed for the past 2000 years. It is the oldest living theatre in the world. You can sit anywhere in a Koothambalam (temple theatre) and hear the performers during a Koodiyattam performance. Kathakali is more accessible than Koodiyattam. There are a few in Kerala who have seen the full act of a play in Koodiyattam which usually takes between 15-45 days to perform. It survived because it was confined to the Chakyar community in Kerala, who were the custodians of this art form.”

Adoor often says when a Koodiyattam performance begins, everything around it ceases to exist. It was largely owing to the efforts of noted scholar Sudha Gopalakrishnan that Koodiyattam was recognised by the UNESCO as “Masterpiece of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity”. Adoor’s three-hour long documentary on Koodiyattam had the UNESCO team enthralled. He adds, “Koodiyattam artistes were extremely demoralised because there were few opportunities to perform and almost no audience. Kathakali on the contrary witnessed a steady ascent. Kathakali artistes were travelling all over the world and being handsomely paid. UNESCO sent a member of their team to Trivandrum to see my film. After the recognition, things are much better now. Money has been granted to the performers and several revival efforts are already underway. I feel gratified.”

The revered filmmaker insists that the audience watching his films should feel that they are watching a performance on stage. He is not a fan of abstraction in art-based documentaries. Adoor feels that dance films must convey every bit of aesthetics of the form which has also been a perennial quest in these films. His preparation for such projects is also meticulous. The Mohiniyattom documentary took around seven years to make. Adoor read every possible book available on the dance form and also saw some of the earlier films made on the subject. He chose to eschew background commentary and interviews. The focus remained on dance as it should because that perhaps is the origin of all dialogue.

Kunal Ray teaches literary and cultural studies at FLAME University, Pune and regularly writes on art and culture.

Topics

Business Finance

IANS Last Updated at May 8, 2018 17:06 IST

More than 25 years ago, the Indian government decided to put together a National Policy of Culture in keeping with more than a hundred countries that had such policies. In fact, there was, at that time, a special division in Unesco which had already organised two world conferences on the matter. Here too a national colloquium on culture policy was organised in 1992 in Delhi in which nearly a hundred writers, artists, performers, intellectuals and experts debated a white paper, which, as the Joint Secretary of the Deptartment of Culture, I had prepared.

The move, however, evoked controversy and the main issue was that state could not set a policy for culture which is the business of society as distinct from the state. This issue completely ignored the fact that the National Culture Policy document tried to delineate a policy framework for the cultural institutions and activities such as the Archaeological Survey of India, the three national academies, the National Museum, the NGMA, the National Archives, the National Library, et al, which are publicly funded and are run largely either as adjuncts of the Indian government or as autonomous institutions such as the Lalit Kala Akademi, the Indira Gandhi National Centre of Arts and the Zonal Cultural Centres, among others.

Also, one key element of the National Culture Policy was that the government's expenditure on culture must, over the years, rise to one per cent of the total budget of from a dismal 0.1 per cent.

The National Culture Policy went through a series of consultations, including by a Parliamentary Standing Committee but was nearly forgotten, if not given up, by 1997. Later attempts were made to revise, review and re-present it, but nothing much happened. In the meanwhile, a government is in place which has been very assiduously and relentlessly trying to cut down allocations to cultural organisations and giving them, if at all, only to those whose loyalty to its ideology it could be sure of.

All arts have been reduced to expensive public spectacles and a lot of public money is being wasted on them without them contributing anything to the enhancement of culture, its dynamic creativity or adding to the broader public awareness of culture.

Increasingly, for instance, the three national akademies have reached the brink of utter irrelevance and have almost no truck or dialogue with excellence.

It is in this context that we have to locate the availability of public resources for culture. They are evidently dwindling and, in any case, the State is well set on withdrawing substantially like in the education and other welfare sectors. One of the more dependable sources could have been the corporate sector whose presence on the map of support for culture is rather minimal and quite disappointing.

A recent survey of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) initiatives shows that quite haltingly the mandated CSR has moved in the sector of culture. There too it is presumably spending no more than maybe two percent of its expenditure on culture. The areas which attract the bulk are health, education and environment. Many major firms have already set up trusts or similar "cultural" organisations and they spend whatever little they do on culture through them.

In most advanced countries culture is considered rightly a civic need and activity and civic agencies such as municipal committees and corporations spend on museums, auditoriums and the like. In this area, the performance of these civic bodies in terms of support for culture is abysmally low and marginal. Sadly and most unfortunately, the State, the civic bodies and the corporate sectors are comrades-in-arm in undermining and neglecting culture.

If in this highly deprived and despairing scenario there is a vibrant cultural climate in the country it is largely due to personal interest, commitment and initiatives of the creative community. Private art galleries, publishers, theatre groups, small non-commercial journals, literary organisations, music circles and sabhas, dancing groups, etc., have kept alive the rich, complex, celebrative but equally interrogative cultural creativity and imagination, investing them with energy and courage, commitment and hard work.

There are some either private or corporate initiatives such as the ITC Sangeet Research Academy Kolkata, the Darpana and Kadamb Ahmedabad, the Raza Foundation, the Cholamandal Artists Group, the Mahagami Aurangabad, etc., which have been supporting various aspects of culture. Sadly they are not many and, in any case, far short of the vast needs of a great civilisation.

(In this concluding article in our Shifting Sands of Culture, Ashok Vajpeyi reflects on the role that state plays, or should play, in promoting cultural activities and institutions. Vajpeyi is a well-known writer in Hindi, and has published over 23 books of poetry, criticism and art. He was awarded the Sahitya Akademi Award in 1994 for his poetry collection, "Kahin Nahin Wahin")

--IANS

vajpeyi/ss/vm

Volume XXXVI No. 2 April – May 2022

Panchaatmika—A Harmony of Multi-Classical Dance Forms

IIC DIAMOND JUBILEE CELEBRATIONS 2022:

Inauguration of the year-long celebrations Welcome by Shri N.N. Vohra, President,

IIC Talk by Hon’ble Shri Ram Nath Kovind, President of India

Vote of Thanks by Shri K.N. Shrivastava, Director, IIC 18 April 2022

The evening performance celebrating the beginning of the IIC’s Diamond Jubilee echoed the spirit of the inaugural address by Shri Ram Nath Kovind, President of India, who said that ‘here divergent views are accommodated with intelligent dialogue’.

Panchaatmika, conceptualised and choreographed by Parvati Dutta of Mahagami Gurukul, was a harmony of multi-classical dance styles. Shiva, comprising the five syllables Na, Ma, Shi, Va, ya, representing the five cosmic elements, Earth, Water, Fire, Vayu and Akash, was artistically and metaphysically envisioned as ‘realising the five-fold universe within oneself’. Contemplated upon through the revelations of oral, textual and performance traditions, involving the five senses, and through a movement tapestry involving the five-fold rhythmic designs through tala (metric) cycles made up of multiples of 3,4,5,7 and 9 units, the work was a harmonious weave uniting the anga-bhasha of five dance styles— Kathak, Odissi, Bharatanatyam, Kuchipudi and Mohiniattam.

Starting with sonorous notes of Raag Vibhas (from Bhairavi thaat dedicated to Shiva) with two singers and mnemonics recited with tabla, pakhawaj, mardal, edakkya, mridangam and khanjira percussion, set to khanda jati (multiples of five), sensitive choreography right from the opening scene, revealed delightful group patterns with multi-styled dancers, hands held high in Anjali. Through Adi Sankara’s Shiva Panchakshara Stotram ‘Nagendra Haraya’, homage to ashsmeared, blue-throated Shiva, wearing a snake garland, with Mandakini on his head, holding fire and trident in opposite hands. Raga Natabhairavi, evocative of contrary moods, with Udukkai phrases, ushered in dancers holding metal bowls smoking with incense, conveying the idea of void for the sequence on Akash, a canopy of nothingness defying definition, extensive and all pervasive for Satkhandagama and a vacuum for Dhammasangani. Its seven-fold lakshanas, says the Mahabharata, are enshrined in the notes shaddja, rishabha, gandhar, madhyama, Panchama, daivat, nishaadh. The substratum of sound produced within, Akash is set to solfa passages, and Sankeerna Jati (metric cycle of nine units needing a sum of matras), dancers moving in perpendicular formations signifying travelling sound space. Music evoking the difficulty of mapping voids, uses Dhrupad, Kharaj, Sarangi, mnemonics of Buddhist Bowl marking the ‘sama, with percussion instruments duf, Tarpa, morsing.

The Natya Sastra traces the origin of Jala Vadya to a Shivagana who, with Viswakarma’s help, created a percussion instrument sounding like rain drops falling on Lotus leaves. Commentator Abhinavagupta described Shiva as Jala murti. Set to tisragati (metric cycle of units of three), and Miya Malhar (the monsoon raga), dancers in graceful steps danced to the sonic rhythm of mardal, pakhwaj, Dug, Khol, Ghatam and Tung Tabla. 2 The Mohiniattam dancer’s entry heralded the sequence on bountiful Prithvi (Earth), dark coloured Mother and life bearer, in white garment, to Chatusra Jati (multiples of four), and raga Jaijaivanti, evocative of joy and negativism. Described in the Vishnudharmottar as endowed with the five perceptions: shabda, sparsha, rupa, rasa and gandha, involving the sense organs, the very basis of all art, dancers move, tracing floor space in a square around a square, the geometry symbolising Prithvi, dancing to the sounds of earthy instruments like dhol with sarangi, udukku, mardal and morsang—an expressional whiff conveying five perceptions of touch, smell, hearing, sight and taste. Symbolising dynamism, powerful but invisible, gloriously riding a chariot in unfettered freedom, set to Misra jati (units of seven), is Vayu, breath of the Gods and life germ of the Universe. Sangeet Ratnakar mentions the part Vayu plays in wind instruments like the flute. Melodious flute music plays a contrast of a definitive misra jati chhand as against just notes in a spiralling enchantment of sound space. Rag Marwa and forceful khandajati (units of five) characterises Agni (fire) the vital force dispelling evil, initiated in the nabhi and rising in an upward triangle to activate mind and speech. Prana and Agni unite in creating Naad. Less than fair to such an aesthetic, painstaking dance venture, was the depleted audience following inexplicable delay in ushering the cultural programme post-inauguration, with daylight killing lighting effects.

LEELA VENKATARAMAN

Emerging cultural economics in dance

- Navina Jafa

Dancers, both classical and folk, urban and rural, have endured severe economic and artistic challenges during the pandemic. Many, however, have slowly embarked on imaginative journeys to reconstruct, reinvent, and reposition their work to align with the emerging modernity and altered performance landscapes.

Crucial to this process is the devising of models that ensure sustainability of performing arts and artistes. Dancers are beginning to see the need for realistic frameworks and practical strategies to reconnect with paying audiences and to navigate their dual existence in online and offline performing spaces.

More than ever, there is an urgency to recognise not so much the formal as the large non-formal creative sector and, therefore, to develop sustainable cultural economics models around this idea. It is also about recognising that potential target audiences today are under 50 years of age and are mostly online and not offline.

Even when auditoriums open, therefore, online performances will continue to remain attractive for funders and sponsors. This is not to say that astute marketing strategies will not materialise offline as well.

Traditionally, the performing arts in India have never applied economic analysis to their industry, with funding, ticketing and sponsorship being mostly ad hoc affairs. In turn, the government has made no effort to explore how culture might be structured as an economic sector; or to map and match the ‘producers’ of the cultural product (performers) and the ‘consumers’ of it (audiences); or to organise state-of-the-art production spaces, technical support, and other infrastructure that can sustain this economy.

What we have instead are a few attempts that are more about ensuring the sustainability of individual practices and have low wider impact, but they are a good start. Of these, the work of four artistes is worth mentioning: dancer-choreographer Aditi Mangaldas, dancer-producer Anita Ratnam, contemporary dancer Surjit Nongmeikapam (Bonbon), and dancer-choreographer Parwati Dutta.

Their work during the lockdown has included not just creative revivals of old works and the creating of new ones but also active engagement with patrons to ensure sustained interest in their art and financial contributions to it. Their initiatives could inspire bolder models for monetising the performing arts.

diti Mangaldas, a first-generation performing artiste, is from a business background. With the team of artistes in her dance company, Drishtikon, she wanted to build a ‘creative component’ during the pandemic. While financially sustaining her team, she initiated a strategy that demanded discipline and immersion from them. “At 10.30 a.m. every day the artistes are there online with their dancing bells, and encouraged to re-imagine their aesthetics,” she says. Aditi also repackaged several old productions as films and marketed them to essentially international networks.

This model, by skilfully weaving technology with art, promises to sustain a global market even in a post-pandemic future. Aditi also conducted inventive workshops and participated in other offline interactions as ways to support her organisation and the artistes associated with it, both economically and creatively.

Anita Ratnam too comes from a business background and is a first-generation professional dancer. “My first experience of cultural economics was in the 1980s, when I was the only television producer to present the Festival of India in the U.S.,” she says.

She was also inspired by her guru Adyar K. Lakshman, who acquired the backing of an affluent Tamil diaspora, especially Sri Lankan Tamils, in Australia and Canada. Anita has used the idea of the diaspora to identify potential audiences and artistes.

Her study showed that viewers were young, and Indians plus NRIs. So the performances were a mixed bag of classical and contemporary. She used the idea of being confined at home to create themes like ‘Boxed’. Her recent series, ‘Andal’s Garden’, encouraged dancers from various genres worldwide to explore the same theme.

Anita also offers hand-holding to dancers for technical aspects like camera and light angles and for aesthetic aspects like costumes and make-up for online shows. Such mentorship creates a larger base of performers and improves the quality of the product, thus making paid shows more feasible.

Unlike Anita and Aditi, Surjit Nongmeikapam and Parwati Dutt are first-generation dancers from middle-class families. Instead of honing his skills in classical Manipuri dance, Surjit travelled to Bengaluru to learn Kathak and contemporary dance at Maya Rao’s Natya Institute of Kathak and Choreography.

“The pandemic threw up challenges of survival. I reached out to several individuals and organisations for donations, many of them from my international circuit, to feed the performing artistes in my organisation, Nanchong Art Foundation,” says Surjit. He renewed connections with patrons and strengthened stakeholders to sustain his work and organisation.

“I work with nine or ten creative professionals — dancers, writers, martial artists, musicians. The contemporary is not a recognised genre, but in the lockdown, I had opportunities to be a part of webinars and virtual festivals,” he says.

Surjit’s last production before the lockdown was the 30-minute ‘1 Sq Ft’, a powerful narrative of human displacement, war and violence, which ironically echoed the crisis of migrant workers that would soon be enacted across the country.

Surjit’s target audience is young, and he is conscious that his work might appeal more to the educated, urban and thinking consumer, but equally that could perhaps make his online sustainability that much smoother as well.

Parwati Dutta grew up in Bhopal but started her work in the completely unknown cultural terrain of Aurangabad in Maharashtra. “I built my institute, Mahagami Gurukul, from ground zero and also partnered with the Mahatma Gandhi Mission.”

The pandemic motivated her to approach her patrons for financial help. “I understood the impact of my work when the people of Aurangabad eagerly supported my donation campaign for artistes and continued to be a part of my online talks on the arts. I focused on the pandemic’s psychological impact in my talks,” she says. Such was the influence on the community linked to Mahagami Gurukul that an engineer was inspired to create a dictionary on sculpture called Shilp Kosh, she says.

Parwati also created an outreach programme in a rural area called Baagh Talaaw, near Aurangabad, with a few settlements of itinerant grazers. She also organised for citizen groups to interact with folk performers of the area, engaging both with their art forms and via survival kits.

“Cultural economics is about investing in creating strong local patronage by building a sense of ownership. That is the way forward. I believe in creating the taste for art among audiences. Their support during the pandemic indicated their involvement in our institution and illustrated that they are part of our larger family,” says Parwati.

The writer is a Kathak exponent

and cultural critic.

| Evolution of dance - over aeons, everywhere Photos courtesy: Mahagami June 7, 2022 Dance has generally been recognized by the cognoscente as an embodiment of the rhythmic, harmonic and aesthetic expressions that man could achieve in his relationship with himself and with the wide open world since the very time of Creation. Indeed, once the arboreal monkeys came down on the solid ground on their two feet and liberated hands for numerous other functions, they became Homo erectus and could make many gestures and create arbitrary patterns and movements. Generations later evolved the Homo sapiens - that is, the modern we - with our all-embracive cultural heritage, including that of dance. [Some scientists have also predicted that we are evolving now into Homo Deus (God-like beings), with our manifold enhancement of thinking power by connecting computers to our brains through information technology as well as enhancing our physical prowess and resistance to all diseases through highly superior biotechnology. One wonders if these would include evolution of a Meta-verse of arts with Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning (AI/ML), and create a new kind of Virtual Reality and Augmented Reality (VR/AR) where new dance movements could be created and seen in an immersive technology, as are already being done for style designs!]  Early man Dance 360 Degrees: Sarvatra Nritya, an ambitious programme, presented by Mahagami University, Performing Arts Department, on the World Dace Day (April 29), offers a unique comprehensive vision into the origin of dance. Conceived and directed by their gifted Dean, Parwati Dutta, the curtain-raiser, Scene 1, finds the bemused dancers observing every activity of Nature with curiosity and confusion. It is as though the humans, as the new denizens of earth, are trying to "learn" from every encounter, experience and effort. This is the pre-history of three lakhs years ago: cognition of the five sensory perceptions of Roopa, Rasa, Shabda, Sparsha, Gandha... Dhun-te-ta/dhun-ta... man is daily taken to new discovery, new quest, new questions, new revolutions, new truths. He tries to follow the flow of life, the pace of life, cycle of life by observing animals and birds. It is the life of hunter-gatherers: by collecting as gatherer and consuming the fruits and vegetables; and surviving as a hunter, having observed carnivores living on their prey. There is no language, no source of communication, no script, no shelter, no ability to comprehend any principle of nature. Man tries to observe carefully every movement, every change of seasons, and stars thinking: How do these acts unfold? Who is doing this? Who is the creator, our fosterer? Where do I find him? Scene 2 begins with resonance of ghungroos, heralding rain. Upanishad's verse resounds: Truth lies concealed in a golden mound / so do you, O sun! / Open the entry to that cover / Be visible to me / A devotee who is truthful by nature / in the light of your illuminating grace...Dancers are in a prayerful mood. Then begins the mind boggling circumambulation of the immense universe of knowledge, one by one.  Parwati Dutta "Philosophy" is ushered in first as an inspired narrative, "How can dance be a way of knowing? It moves and it changes... There is an impermanence reflecting the absence of stable art objects. Is dance an ephemeral art? Philosophers don't perceive thought as a purely intellectual activity, but as a two-way dynamic exchange between the world and the active perception of an individual. Dance then can be a model path of thinking itself..." On the forestage is contemplative dance in Kathakali mould, with silhouettes of playing mizhavu in the background. "Psychology" flits in with bhava, rasa, but is given a short shrift. "Physics" comes in then with the narrative on dance technique, dynamics, centre of gravity, like the solar plexus (a favourite point of Martha Graham). Odissi and Kathak dancers demonstrate poses and postures: the vocabulary of lifts, spins, leaps, turns, balance, central axis, gravity, with laya, speed, tempo. Momentum reigns: angular momentum, angular velocity, centrifugal force, centripetal force, torque. It appears to be director's favourite! "Geometry" follows where dancers move as the narrator speaks, but not much. The narrative resounds, "A dancer's body is the source and the medium, for various shapes, forms and dimensions in the 2-D and 3-D space. A man can observe own shadow cast on the floor at varying points of time in the day, or against a water body, or on a reflecting surface: to define a thesaurus of forms by changing the way to stand, bend, sit, fall ...A dancer's body can stand erect to create a straight line or use a slight bend to create a chiaroscuro of curves... Lines and curves transform into crescents, spirals, spherical... By maneuvering joints and ligaments, the dancer understands geometric forms: Anga, pratyanga, Upanga... "Cosmogony/ Astronomy" is again a narrative on the universe, where celestial bodies dwell in an orderly way. The voice goes on, "The celestial bodies move in an orderly way. The direction, path, pace and purpose seem to be defined. Time taken by Mercury to complete one solar orbit is four times the duration of earth, while Venus takes one and half times that of earth..." The dancer displays these through time-cycles and laya sequence. The narration moves to "symbolism": connotations of movements, positions and stances. A solo dancer uses Kathak, accompanied by Dhrupad, interpreted as Dhyan, with 'Om' as in meditation.  Environment "Environment" - with sounds from Nature in Gurukul, and utterances of animals and birds that follow these sounds -- is among the most inspired part of the programme -- like 'dhalang' for a lion's leap; 'jhijhikita' for the crickets; 'jhanak jhanak' for sound of ghungroos; the little bird's quest for water to quench her thirst after the rains; and so on. A male/female duo does a wonderful job of mimicking, followed by the Jalabindu song in Sanskrit sung with Odissi. "Design" is yet another delightful segment, with multiple ways of designing and redesigning space and time, and numerous ways the body can be used. An example is Matraa as the smallest unit and Bols come as symbolic structures as the building blocks, creating designs with rhythms. The dancers execute Tihais showing Gopuchcha and various Yatis on stage. "Communication" is yet another striking part in a long programme, highlighting verbal, non-verbal, interpersonal and intrapersonal aspects. With a popular Odissi composition Pratibimb (Reflection), three female dancers look into a mythical mirror using many motifs of a Pallavi in raga Jog showcasing all the four motifs fascinatingly. "Anatomy" follows, with the narrative highlighting limbs, joints, flex, stretch, twist, compress, et al. Dancers show preparation of the body through warm-ups, cool downs, stretches, healings... By far, the most fascinating part is "Architecture", with its wealth of illustrations from temple sculpture where the architect visualized it as a human form. A solo Odissi dancer presenting Mangalacharan enters with a unique Chali suggesting the idea of climbing steps in a sacred space. The full turn of the dancer marks the Nandi Mandapa and presenting the Bhoomi Pranam, points at the deities of Jagannath, Subhadra and Balabhadra. After offering Pushpanjali, she defines the arches in the eight directions and the imaginary arches. The dancer concludes with Trikhandi Pranam and the coordinates -- pointed at and defined by the dancer -- creates a virtual architecture out of Shoonya (the empty space). "Arithmetic" comes then, and the idea of aligning a rhythmic phrase in various speeds and multiples (as in Kathak) is just the beginning of the idea of arithmetic. Tihai is a composition that has calculations differing for odd numbers, even numbers, prime numbers. Tihai has many variants - Farmaishi Chakradhaar, Kamali and so on, making 'dha' as a determinant for various segments. "Metaphysics" as a branch of philosophy dealing with nature of existence, truth and knowledge, is then taken up by three Odissi dancers to illustrate how dance can be continually renewed by creation of new movements. The narrative continues: Art is not something separate from the "being" of the artist, but it is the quintessence of her existence, manifest through a skillful practice of her art. In this practice, the two extreme states of existence - spirit and matter generally perceived as opposed to each other - completely coalesce under the harmony of body, mind and spirit. For "neurology", the narrative brings out how dance induces subtle changes in the brain through a process known as plasticity, which induces the brain to adapt in response to experiences. While many elements of a rich narrative cannot be illustrated by a full performance due to sheer pressure of time, they are simply given as a demonstration. "Aesthetics" and "sculpture" are, however, beautifully illustrated with the cyclorama lit up by magnificent visuals of temple friezes and human figures sketched by early Indian and Italian painters, while three Odissi and three Kathak dancers evince their skills, vibrant with movement, rhythm and expression. The interaction of the movement structures and interrelationships of the components of the dance are captured in a Jhaptal Tarana that highlight the aesthetic beauty of Kathak, while Odissi presents excerpts from Batu Nritya highlighting the sculptural poses of Odisha temples through various Bhangis like Mardala, Parshva Mardala, Alasa, Darpani... "Painting" narrates how both space and time act as a canvas to the dancer while the dancer traces various strokes, shapes, forms in both space and time. She creates cadences of painting through lines and colours of emotion and energy through synergy of forms. "Calligraphy" brings out, in the narrative, how the script of Maheshwara Sutra was created by notating Shiva's crescent-like movements as he danced holding damaru in one hand. Dance is the mother of the art of writing. Since calligraphy is an art of creative arrangement of letters, the performative art of dance has an element of spontaneity at its core. For both, the finished product seems fluid and random, but, in reality, each part - even a single stroke - is choreographed, intentionally made. In both, fluid lines seem to mimic the energy and appearance of Nature: the constructed line is no less true than the natural one. Finally, each word in a finished piece is self-contained, an independent spatial experience; similarly, for dance, space is a static condition whereas spacing is an active process. Parwati herself takes the stage and her Kathak performance - based on excerpts from Varnajaa -is superbly dignified. "Nourishment / well-being" talks about nourishment of body, mind, soul, while dance stimulates metabolism, cardio-vascular and neuro-muscular activities. "Yoga" is chitta-vritti-nirodha, whereas dance is Yoga itself. Indeed, Natya Shastra invokes Shiva as the ultimate dancer and Paramayogi. "Immunology" relates to Sattva, Raja, Tama... away from toxic thoughts and polluting ideas. These disciplines are only touched upon.  Mythology "Mythology" climbs to rare heights, representing power and divinity through dancing forms. Five Odissi dancers depict Shiva as the cosmic dancer, with his four arms and flying locks symbolizing a multitude of ideas. The idea of creation and destruction of the cosmos is symbolically and metaphorically narrated through legends that form the foundation of dance offerings, guiding the society towards righteousness. The great mythology of Dashavatar is enacted in full in Odissi.  Poetics in dance  Dance as Language "Literature / Poetics" comes next, depicting excerpts from Chitra Kavya and Vilom Kavya. "Dramatics", the oldest way of looking at dance is taken up next, with performance from Kalidasa's Ritusamhara, bringing out elements of drama. "Language" follows, illustrating how a dance tradition is equipped with codified gestures around which a world of movement language is created. Some examples are enacted from Abhinaya Darpana on Hasta, Shira, Griba, followed by words, phrases, sentences depicted in dance language.  Hasta abhinaya  Ovi of Maharashtra Then comes "Sociology". For primitive peoples, dance was their principal form of communication: not merely as corporeal movement, but also for connecting the humans to their gods. Dance represents the symbols and meanings of how social groups live. Jaatyavarch Ovi sung by village women while performing daily chores was presented in Kathak. "Value Education" follows, where dance plays an important role in instilling values in the learners in an oblique way. Dancers present an excerpt from the earlier Mahagami production Sutra Atman, dedicated to Mahatma Gandhi, depicting 11 resolutions of Gandhiji that he followed in his struggle for awakening the country. "Vadya Kala" is an endeavour where the dancer - with her body as the medium and ghungroo as the instruments - weaves various footwork patterns in Kathak to represent the idea of dance as music; dance as melody; dance as Vadya. "Archaeology" comes as a reminder that a dance practitioner is a museum of her own art form, where she has acquired, imbibed and simulated a huge body of work, compositions, aesthetic sensibilities, historical facts and traditional knowledge. She needs to value archaeological facts and details with respect to ancient cultures, civilizational symbols and, importantly, information related to dance embedded in ancient inscriptions and artifacts. There is no performance on this topic and on "Management / Administration" that follows next as narrative. Dance represents dynamics and change, and puts the moving body at the centre of activities, which is ignored in the traditional management theory. Yet, 'Leadership' as a quality and as a dialogue is essential in the work of dancers and musicians who happen to manage groups without words.  Spirituality in dance "Musicology" rings out, without a performance, how dance incorporates a detailed insight into music traditions, music practices and musicology. It is interesting to note that Sharangadeva, in his treatise Sangeet Ratnakar, defines Sangeet as a composite term representing music, instruments and dance. In "Heritage" too, there is no performance, yet the narrative is eloquent as to how dance is one of the few art forms that simultaneously embellish space and time. Last of all, "Spirituality" is treated at length. Dance is an intrinsic part of human nature, being able to offer, to communicate, to connect and to elevate one's consciousness. Vallabacharya's Madhurashtakam is taken up in Kathak to glorify many forms of the sublime Krishna. An Odissi composition Om Manipadme Hum - based on Tibetan Buddhist chant -concludes the evening, seeking to sanctify the space around and within. Overall, it is a marathon programme to cover something like 36 disciplines of knowledge systems found around 360 degrees of gazing around! Hats off to the director for her bravery, consummate devotion to artistry and, above all, a near Spartan daredevilry in attempting to be so comprehensive!!  Dr. Utpal K Banerjee is a scholar-commentator on performing arts over last four decades. He has authored 23 books on Indian art and culture, and 10 on Tagore studies. He served IGNCA as National Project Director, was a Tagore Research Scholar and is recipient of Padma Shri. |

30 years of ASEAN-India ties celebrated at Udaipur The 9-day camp included artists from ASEAN countries Indonesia, Philippines, Malaysia, ...